CURATED BY

Hyunjin Kim

PAST

GALLERY HOURS

Wednesday–Saturday, 12–5 pm

Free Admission

Proof of vaccination and masks required

KADIST San Francisco

3295 20th Street

San Francisco, CA 94110

www.kadist.org

KADIST

San Francisco

Frequencies of Tradition centers on tradition as a space of contestation. Tradition is a significant part of daily lives in Asia, connecting generations and reverberating as a living archive of cultures across time. Tradition also retains and upholds patriarchy, authoritarianism, and obsolete customs. Through collective memories, spirituality, archival imagination, technological engagements, and alternative modes of empowerment, the works in the exhibition—predominantly video installations and photography—upend conventional notions of tradition and examine how regional modernization entangles with the emergence of tradition and where the violence of social conventions, nationalism, and the impact of such histories on the everyday manifest. Together, the works allow for a critical reflection on modernization in East Asia and where an expansion of our understanding of the regional modern takes place.

Frequencies of Tradition at KADIST San Francisco is preceded by its large-scale iterations at the Guangdong Times Museum, Guangzhou, China (2019-2020) and Incheon Art Platform (2021-2022) and is the culmination of an eponymous series of exhibitions and programs initiated by KADIST in 2018 and curated by Hyunjin Kim, KADIST’s former Lead Regional Curator for Asia (2017-2020).

Comprising seminars, commissions of new works, and exhibitions across Asia, Frequencies of Tradition is a three-year series as part of KADIST’s international programs devoted to drawing connections between different localities by addressing shared issues, often of global relevance, in close collaboration with partner institutions, researchers, and artists in the region.

ARTISTS

Chung Seoyoung, Yoeri Guépin, Ho Tzu Nyen, Chia-Wei Hsu, siren eun young jung, Tomoko Kikuchi, Seulgi Lee, Young Min Moon, Hwayeon Nam, Gala Porras-Kim, Lieko Shiga, Ming Wong

And a screening program featuring

Fiona Tan, Jane Jin Kaisen, Wang Tuo, siren eun young jung, and Ko Sakai & Ryusuke Hamaguchi

CURATOR’S ESSAY

On Frequencies of Tradition: From Ghosts of Modernity to Spirits of the Ungovernable

Hyunjin Kim

Tradition is still a prominent and practiced form of daily life on the Asian continent, connecting diverse generations, transmitting community values, and serving as a living archive for cultural posterity. On the other hand, tradition also retains negative perceptions as a source of patriarchy, authoritarianism, hierarchy, and outdated customs. Frequencies of Tradition challenges the understanding of tradition as a space of contestation, providing the tools to critically reflect on East Asia’s accelerated modernization. Presenting works by sixteen contemporary artists, collectives, and filmmakers, the exhibition explores tradition as an enchanting and liminal space that complicates and interpellates our understanding of the regional modern.

The works in the exhibition rely on unraveling notions of tradition—the art of narrating and reenacting the old; ancient and ancestral symbols which bring a sense of belonging and spirituality; and cultural ordinances which sustain and stimulate a community’s belief system—in order to relay strategies of ongoing cultural production and to shed light on the substantive nature of tradition as a source of vulnerability and transformation. Despite the tropes, traditional constructs have been further refracted and complicated through prisms of pan-Asianism, Orientalism, Cold War ideology, and nationalism. Nonetheless, nostalgia evoked by significant social changes in modern time recalls and provides an impetus to uphold tradition. Seen as a relatively recent phenomenon, Eric Hobsbawm argues that tradition is the invention of modernity, becoming entangled with significant parts of the modern nation-state building process of the 20th century.1 Tradition, thus, has proven a useful tool for forging a sense of community, national cultural identity, and even towards the practice of patriotism for those living enmeshed in historical, ethnic, economic, or religious differences.2

The economic achievements of countries in East Asia, such as Japan, South Korea, and China, were accelerated by the governmental adaptation of aspects of Western modernity, especially Western industrial infrastructural development. Therefore, it can be argued that westernization has always been synonymous with East Asia’s modernization. For the region’s inhabitants, as noted by the renowned Chinese scholar of East Asian studies, Sun Ge, the geopolitical conception of Asia—between the biopolitical concept of race and otherness and the geopolitical concept of locality—was constructed by the time the West began to invade. Whereas Edward Said argued that Western Orientalism originated in the vein of Western self-centrism. Sun Ge, conversely argued that what became the antipode of Asia was not the West, but in fact, the figure of the West—a self-made construct generated to promote the discursive cultivation of “Asia” and its colonization in its dynamic complexity with the West.3 Since the latter half of the 19th century, the Japanese elites and intellectuals who sought to emulate the West immediately after the Meiji Restoration strove to construct “Asianness” as a counterpoint to the image of the “West.” From early on, emphasis on the uniqueness of “Asian” values or spiritual symbols, including the separate discourse of pan-Asianism, knotted “Asianness” to associations with images of the sublime and mystical, such as the lofty Himalayas (Okakura Kakuzō emphasized this as the integrity of two supreme pillars of Asia—Chinese Confucianism in the north and Indian civilization in the south), Kegon Falls, Nikkō, Japan (which one of the Kyoto School scholars illustrated as the towering symbol of Japan in the world history), and Mount Fuji.456 “Non-modern”, elements such as the purportedly primitive nature of Zen Buddhist philosophies, were instrumentalized as Asian spiritual tradition under Japan’s Pan-Asian ambitions. They were also wielded as tools for collusion in the Pacific War through Japanese militant nationalism.

Such a context is tangential to the absorbing narratives in Ho Tzu Nyen’s Hotel Aporia, (2019) which provides a glimpse into the lives of historical characters including Kyoto School scholars and their philosophical arguments over the notion of void (왕, or 虛無), and members of the Kamikaze unit during the Pacific War. Based on Zen Buddhist thought, the Kyoto School is noted for having popularized philosophical debates which delved into issues of Western canonical hegemonic ideology at the time. However, despite their significance, members of the Kyoto School were considered condemnable as intellectuals for justifying Japanese imperialism in China and other parts of Asia. They managed this by way of secret meetings with the Japanese navy. During a Chūōkōron (a monthly Japanese literary magazine)-organized symposium “The Standpoint of World History and Imperial Japan” on November 26, 1941, one of the Kyoto School scholars, Kōyama Iwao presented the notion of Japan’s spirituality and history as compressed into the image of the Kegon Falls in Japan, arguing that the nation was the new protagonist of world history. In addition, and to add to the growing hostility towards members of the Kyoto School, one of its prominent members and scholars Tanabe Hajime gave a lecture about “Shisei [Death-Life]” (1943) which wielded immense influence over young Japanese men such that many volunteered themselves as suicide Kamikaze bombers for the war.

To continue the theme of symbolic ascription and making Japanese world history, Fiona Tan’s Ascent (2016)*, as part of the off-site screening program, is a visual study of Mount Fuji, revealing the religious and cultural significance of Mount Fuji and images of the mountain as produced and consumed by modern Japanese militarism, Japanese society, and individuals. The work consists of 4,500 still photographs of Mount Fuji taken in the past 150 years and follows a fictive dialogue between two protagonists, one of which speaks positively on the concept of “void” in Japan considering it as something that can be “filled,” resonating with the philosophical concepts of “nothingness” and “void” unique to the Kyoto School.

In South Korea, as the nation initiated and accelerated industrial modernization during the latter half of the 1960s, a military dictatorship oppressed and launched a movement to eradicate age-old, traditional religious forms such as shamanism despite the fact that they were deeply embedded in people’s daily lives. At the same time, however, the regime was selective about which “traditions” got a pass and were allowed to remain based on their ability to preserve and maintain the state’s cultural and spiritual competitiveness through modernization and through institutionalization. The vicissitudes that tradition underwent in Asia in the latter half of the 20th century, when statism and Cold War ideology were one and the same, were also grounded on the utility or negativity of tradition as an ideological device. In 1966, amidst the Cultural Revolution in China, Confucian traditional culture was viewed as a feudal remnant. Meanwhile, books, artworks, handcrafts, and Chinese opera were condemned, as well as numerous historical and architectural sites such as temples, palaces, heritage buildings, considered of an outdated era. These monuments were considered part of an obsolete culture and were subsequently destroyed by the Red Guards, young people who organized and mobilized for the far left populist movement and guided by Chairman Mao Zedong between 1966 and 1967. Prior to that, the Taiwanese government ran “reverse-mirroring” of divergent cultural policies like the Han ethnic-centered “Cultural Reunification” (1945-1965) and the Chinese Cultural Renaissance Movement (1966) to strengthen the discourse on traditional Confucian culture.7 In South Korea in the 1960s, the dictatorial military regime was pursuing the preservation and institutionalization of tradition while proclaiming “nationalist democracy.” This was a political agenda to gain ascendancy over South Korean intellectuals based on Western liberal democracy as well as North Korea’s communism. Thus “tradition” in Asia came into fruition through complex ideological tensions with neighboring countries. “Tradition” in Asia, then, can be understood as an act of naming.8 Related phenomena such as the national and ideological reproduction of traditional culture are partly explored in Ming Wong’s Tales of the Bamboo Spaceship (2019), which traces the history of the transition from stage to screen of Cantonese opera martial arts in the 20th century. The video articulates the phenomenon of heroic revivals through the screen in places such as Hong Kong and Taiwan and in contrast to the oppression faced by performers of Chinese opera in mainland China during the Cultural Revolution. The work furthermore stipulates the phenomenon as a history of queer performance, expanding it into a chapter of speculative science fiction.

Chia-Wei Hsu’s Sprit-Writing (2016) summons Marshall Tie Jie, the spirit of a Frog deity who migrated to the Taiwan Strait from a destroyed temple during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Collaborating with local villagers, the artist’s interrogation of the spirit, is reenacted in a 3D space. The movement and sounds of a divination chair are digitally restored, gesturing to the possibility that these technologies can restore temples or holy sites which no longer exist. The juxtaposition of the 3D modeling space and the spiritual chair over the digital matrix brilliantly interrogates the compatibility between non-modern tradition and high-tech modernity as common in today’s East Asian society and daily life.

While this exhibition features several traditional performances and dances from Asia and related portraits of performers and the record of their work, it is far from a mythologization or museological representation frozen in time. Instead, the exhibitionary goal is to bring attention to the particularity of the liminal space of modernity within tradition—to present both a history that distorts artistic aspirations and an enchanting artistic trajectory that exceeds its history.

A video documentation of shadow play, Gala Porras-Kim’s Muscle Memory depicts both the movements of the muscles where traditional dance is remembered and stored as well as the discernment of the dancer by adding her own interpretation to the transmitted choreography. Presenting the body as a locus of transmission, preservation, and interpretation, Muscle Memory provides a dialogue on representation surrounding memory, archives, preservation, tradition, and bodily limitation. Likewise, Hwayeon Nam’s video Against Waves (2019), includes testimony by two Zainichi Korean women learning the dance footsteps of the international diva Choi Seung-hee, on a wavering North Korean ship, a gesture to the strong but precarious aspiration for the East Asian dance of Choi which exists in a liminal space. Further, this secret dance lesson and memory transmission in Choi’s choreographic work Against Waves from 1956 insinuates an ontological vulnerability found in the transmission of traditional dance, with particular respect to the Zainichi Korean community’s precarious life in the context of national and ideological borders.

Tradition continues through communities through the act of intergenerational transmission or else it dies out. The ebb and flow of tradition escape official authorities. Rather, tradition persists through engagement, embodiment, and commonality, as consensus through the community. The works in the exhibition consider this practice as a medium by invoking longstanding traditional methods. Freely adapting artisanal skills and linking vernacularism and universality to aesthetics, Seulgi Lee creates a nubi, a traditional Korean quilt, blanket series in collaboration with nubi artisans in the southern city of Tongyeong in South Korea. Lee’s blanket adopts Korean proverbs that reflect community spirit and satire, translating them into geometric patchworks of witty pictograms.

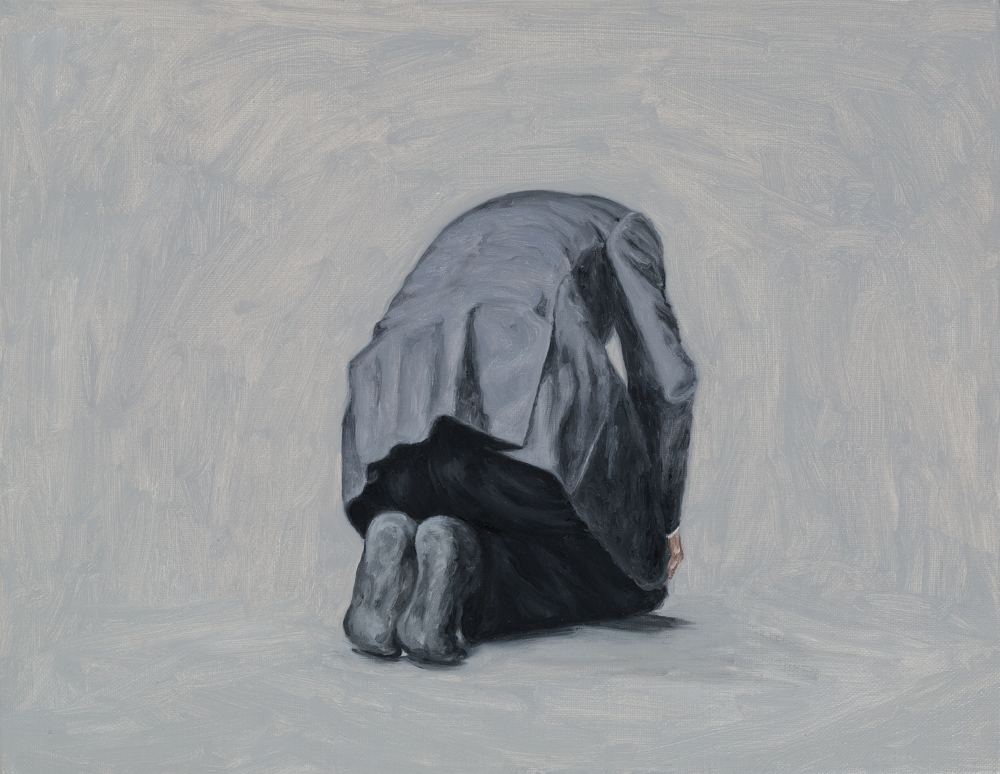

The ruins observed in Yoeri Guépin’s video work Garden of Perfect Brightness (2019) and Lieko Shiga’s photographic series Rasen Kaigan (2009-2021) linger between enchanted and haunted, invoking an emotionally and psychologically complex reality that sways between the modern and the non-modern. Repetitively depicting typical images of Korean jesa (Confucian ancestor veneration rites), such as that of a prostrating man and an offering table, Young Min Moon’s painting series goes beyond meanings forged by tradition and the individual to reveal personal, social, and communal points of intersection that the artist—who has experienced both the modernization of South Korean society and a diasporic life in the United States– holds onto as “rituals,” cast by the shadow of death.

Tradition in East Asia has been known to prolong patriarchic culture and also has been instrumentalized towards nationalism, evident in the nationalist and ideological conflicts inherent to the 20th century. Frequencies of Tradition, however, signals an alternative future to these old stories. Women, LGBTQ2SIA+ community, and the elderly are the subjects and performers of traditions presented. The artworks in the exhibition offer portraits of the figures of unruly women; older generations portrayed as healers in ravaged areas; historical continuity from individuals’ small narratives; and rituals and movements of the gendered other together emerge as fascinating actors and frequencies of unlearning patriarchal traditions and Asia’s male-dominated histories.

The oral transmission of the elderly in Ko Sakai and Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Storyteller (2013)* provides an empowering moment for the Tohoku Earthquake area’s community. We see tradition entangled within the genderqueer community in Tomoko Kikuchi’s photographic series Funerals under Neon Lights (2014), where it plays a vital role in the rituals of funerals in rural China. In siren eun young jung’s Deferral Archive (2018), a fascinating cultural space is revealed where women, previously oppressed by a patriarchal apprentice system,9 create self-empowering moments through traditional performances staged without the accompaniment of men as evidence of a gender-becoming mode in the representation of traditional stories. Deferral Archive (2018) is the archival extension of her decade-long ethnographic research project Yeoseong Gukgeuk Project (2008–ongoing). Yeoseong Gukgeuk, which was popular in 1950s until late 1960s, is a form of women-only traditional theater in the Korean peninsula’s post-colonial liberation social space. Deferral Archive invites us to the mesmerizing queer stories and aesthetics through vibrant wall graphics and color compositions made with first- and second-generation actors’ old photo albums. Juxtaposed are videos of an older generation actors’ performances which convey a gendered and political singularity against the patriarchal stronghold of Asian society.

Jane Jin Kaisen’s film Community of Parting (2019)* calls upon shamanism as an ungovernable indigenous spirit that links two incompatible worlds. Critically reflecting on abandonment, separation, migration, and discrimination over East Asia’s borders of brutal Asian andro-modernity, Community of Parting subsumes the ancient Korean shamanic myth of Princess Bari as an invisible spiritual medium as well as a name of the patriarchical other, for the literary and critical notion explored in the film. Kaisen evokes Bari as a liminal being that transcends human-made borders, and finally consoles the many social deaths of the Other, those who suffered expulsion, abandonment, migration, separation, oppression, discrimination, and trauma, as an utterly empowering mediator of radical ethics and spirituality.

Wang Tuo’s film Tungus (2021)* deals with the history of the Siege of Changchun, which took place in 1948 in Manchuria (present-day Dongbei, China). The film features a scholar and two soldiers from the Chinese People’s Liberation Army who are originally members of the Korean Liberation Army. Amidst extreme hunger, the scholar and the two soldiers experience hallucinations from the past—specifically, the May 4th Movement of 1919 in China and of Jeju Island, South Korea, their home, as well as hallucinations of the massacre committed on the island in 1919. Wang’s lyrical work evokes a sense of community and collective conscience around the shared experience of fear and death. It also summons the collective trauma of colonialism, social movements, and the Cold War. Standing on the boundary between life and death in Community of Parting and Tungus, shamanism can be seen as a hauntological passage that summons specters from East Asian history and prompts them to face and overcome inner scars.

Frequencies of Tradition weaves together multiple nodes and trajectories through the compelling aesthetics of time-based media—video, film, and performance. Yet, speaking of tradition in the contemporary art world still risks being a double-edged sword. While pursuing tradition as a thought-provoking medium in our understanding of the unique pluralities of Asia, the exhibition acknowledges the perpetually precarious position of tradition and its intersection with the status quo’s regional political tensions. Through fascinating collective memories, spirituality, archival imagination, different technological engagements, and empowerment, the exhibition reveals a mode of the ungovernable. While asking how the development, modernization, violence of conventions, nationalism, and norms of such histories continue to manifest themselves and materialize today, the exhibition uncovers the enthralling space found in and through tradition, where one can encounter the vernacular and plural state of Asian modernization. The bodies, singing, chanting, and dancing with sound and rhythm, become a sphere to transmit the memories of community, stories of nature, and the manifold narratives of unwritten regional histories.

*Presented as part of the monthly screening program at the Roxie Theatre, San Francisco (April 20-July 16, 2022).

NOTES 1.Eric Hobsbawm, The Invention of Tradition, ed. Terence O. Ranger, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

2. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, New York: Verso, 1983.

3. Sun Ge, Asia as Speculative Space, trans. June-pil Ryu et al. Seoul: Changbi Publishers, 2003, p. 61.

4. “Asia is one. The Himalayas divide, only to accentuate, two mighty civilisations, the Chinese with its communism of Confucius, and the Indian with its individualism of the Vedas. But not even the snowy barriers can interrupt for one moment that broad expanse of love for the Ultimate and Universal, which is the common thought-inheritance of every Asiatic race, enabling them to produce all the great religions of the world, and distinguishing them from those maritime peoples of the Mediterranean and the Baltic, who love to dwell on the Particular, and to search out the means, not the end, of life.” Okakura Tenshin (a.k.a. Okakura Kakuzō 岡倉 覚힛, February 14, 1863 – September 2, 1913), Japanese Scholar of Arts and traditionalist in the late 19th century stated in his famous textbook, “The Range of Ideals,” in The Ideals of the East: The Spirit of Japanese Art.

5. The Kyoto School is a Japanese philosophical movement centered at Kyoto University in Kyoto, Japan. It seeks to assimilate Western philosophy and religious ideas towards the and use them to reformulation of the religious and moral insights unique to the East Asian cultural tradition. Beginning roughly in 1913 with Kitarō Nishida, the school survived early accusations of fascism and controversies after the Second World War.

6. On November 26, 1941, the Kyoto School introduced the Kegon Falls as the towering symbol of Japan, at the symposium “The Standpoint of World History and Imperial Japan,” organized by Japan’s foremost literary monthly Chūōkōron. The Kegon Falls were already known as the “Suicide Falls,” after a well-publicized suicide of an eighteen-year-old philosophy student and poet in 1903, which later inspired many copycat suicides. For the Kyoto School, the Kegon Falls represented the sublime, and symbolized their idea of assimilating the world into the spirit of Japan, as well as the manifold of what they believed to be the essences of Eastern philosophy, such as (resoluteness, sacrifice, the absolute, and the solemnity and resplendence of Buddhist thought “Avatamska”, or, in Japanese, “Kegon”). The symposium emboldened the Kyoto School, such that it blatantly announced that the Pacific War as well as the colonial invasions of various Asian territories were honorable, which in turn inspired the Japanese youth to offer their services as Kamikaze pilots. The related research was developed and presented by the artist, Park Chan-kyong in his work, Kyoto School (2017) (35mm multi-slide projection).

7. Yun Young Do, “Nationalization Project and ‘Tradition Culture’ Discourse in Taiwan and South Korea in Cold War Era,” in Hyunjin Kim and Hyo Gyoung Jeon (eds.), Tradition (Un)Realized, Seoul: Arko Art Center, 2015, p. 69.

8. Ibid., p. 68.

9. Before the modern education system, a young trainee had to be a long-term pupil of a master to learn traditional skills. Masters were mostly men, and prolonged and unrelated labor was sometimes demanded by trainers and implemented under a rigorous hierarchical system. In siren eun young jung’s research on Yeoseong Gukgeuk in South Korea, sexual and labor exploitation by senior male masters was one of the causes that led some women actors to initiate female-only theater in the late 1940s.

ARTWORKS

WINDOWS

Lieko Shiga*

Rasen Kaigan series, 2009-2021

Large Heart No. 49, 2009

C-print, 47 ¼ x 70 ⅞ in

Courtesy of the artist, KADIST collection

Candy Castle No. 28, 2012

C-print, 47 ¼ x 70 ⅞ in

Courtesy of the artist, KADIST collection

*see GALLERY ONE for details on the artworks

U: Repair the cowshed after losing the cow = Too late, 2018

Korean silk, 76 ¾ x 61 ¹/16 x ⅜ in

Made in collaboration with a Korean Nubi artisan in Tongyeong

Courtesy of Gallery Hyundai Seoul, Seulgi Lee © ADAGP Paris 2022

Korean silk, 76 ¾ x 61 ¹/16 x ⅜ in

Made in collaboration with a Korean Nubi artisan in Tongyeong

Courtesy of Gallery Hyundai Seoul, Seulgi Lee © ADAGP Paris 2022

Seulgi Lee’s U is a nubi (traditional Korean quilt) blanket project that shows Korean proverbs expressed as geometric shapes. Nubi blankets were used as single sheet summer blankets in Korean households until the 1980s; however, they are now turning into obsolete objects as western bedding culture proves more dominant. Seulgi Lee created her nubi blanket series in collaboration with Sung-yeon Cho, a Tongyeong nubi artisan with 30 years of hand stitching experience. Through colors and geometric patchwork, she conveys community spirit and thinking by transmitting the proverbs, with which she titles her works, in the form of witty pictograms. Lee considers her nubi blankets shamanistic sculptures, which are characterized by visual translation of Korean proverbs, protecting and guarding the human bodies against external objects. Lee’s nubi blanket can be summarized by the five colors of obangsaek (traditional Korean color spectrum), which are based on the yin and yang as well as the five elements—simple yet beautiful geometric forms and nubi textures. Depending on the meaning of the proverb, nubi is applied in different directions on Jinju silk known for its excellent reflection of light, and the resulting nubi blankets of U revive past sounds and languages.

Lee’s artistic references range from anthropological materials, linguistic tropes (or figures of speech), and vernacular culture, to handcrafts and the graphic culture inherent to animist systems of knowledge. She collects research materials, techniques, and images for use in her artistic practice, which includes a focus on interweaving the particularities of language, aesthetics, and folk culture. Her continued anthropological interest in the past and the present are expressed through her use of a range of media such as wall drawing, sculpture, object, video, and sound, intensifying her witty and satirical artistic character through geometrical configurations and lively colors.

Tomoko Kikuchi*

Funerals under Neon Lights, 2014–present

Liangzi at the funeral, Sichuan province, 2014

Digital c-print, pigment ink on archival fine art paper, 18 ½ x 27 ¾ in

Bereaved family at the funeral, Sichuan province, 2014

Digital c-print, pigment ink on archival fine art paper, 18 ½ x 27 ¾ in

This project was supported by the Abigail Cohen Fellowship in Documentary Photography, Magnum Foundation & Asia Society (ChinaFile). Courtesy of the artist, KADIST collection

*See GALLERY TWO for details on the artworks

GALLERY ONE

Muscle Memory, 2017

Single-channel video, black and white, silent, 6:10 mins

Courtesy of the artist and Seoul Museum of Art

Gala Porras-Kim’s work is based on her interest in the ways in which institutions view artifacts, objects, and even human corpses considered to be ‘cultural heritage’ dependent on cultural difference. Muscle Memory is a video recording the shadow of a dancer’s muscle movements as they perform a traditional Korean dance. Fundamentally, dancing harbors ontological vulnerability in that it is difficult for it to be transmitted in a perfectly 1:1, identical and preserved manner. Here, a dancing body under shadow retains historical record of traditional dance, while remaining open for the dancer’s interpretation. Porras-Kim has explored how the fields of linguistics, history, and museum conservation deal with formless objects such as sounds, languages, and history in disparate ways, posing questions such as: how do heritage artifacts achieve cultural and historical status, and why are they selected as worthy objects for museological contexts?; how are formless objects incorporated into institutions of officially declared ‘traditions’?; and, how do current motives and understandings not infringe on the lives led by historical object? When the concept of ‘caring for’ collections disagrees with the physical and conceptual frameworks of the objects themselves, which is not uncommon, what can stewardship look like? Practicing works that challenge, intervene in, and make suggestions regarding such institutional limitations, the artist reveals keen insights into the cultural dignity of objects that are sacrificed by diverse institutions within cultural praxis.

Clay Tower, 2013

Pencil on pigment prints, 8 1/4 x 11 1/2 in and 11 1/4 x 16 1/4 in

Courtesy of the artist and Ilmin Museum, Seoul

Chung Seoyoung is an artist who constructs her idiosyncrasies into forms, by sensing the elements through objects that connote or reveal the world around them, into unique sculpture and drawings. Clay Tower consists of faint pencil line drawing over photographic images printed on paper. In the photographs, a tower of clay—which looks like the type of pagodas found in Korean Buddhist temples—has been haphazardly constructed and placed on someone’s knee. The images capture the minute adjustments the man makes in his posture as he tries to prevent the tower from collapsing. This work thus shows the sculptural reality created through the combination of the clay tower and a body. The frozen picture plane captures the changes and mobility in the body and are concealed in the postures used to support the clay tower, as well as in the very moments in which this state is maintained. Connoting the vulnerability or mutual interference in the relationship between the supporting structure and tradition, the work explores mechanism, prop and the concurrent appearances surrounding the miniature, the symbol of age-old cosmologies.

Deferral Archive, 2018

6 Pigment prints and 2 single-channel videos

Dimensions variable

Made in collaboration with Designer Collective dl.tokki.dl

Courtesy of the artist

Deferral Archive is one of the archival extensions of siren eun young jung’s Yeoseong Gukgeuk Project (2008–), a decade-long ethnographic research project into the diminishing genre of Korean traditional theater known as Yeoseong Gukgeuk (큽昑國劇). The genre, which was popular in the 1950s-60s, has since been forgotten, without ever being established as either a traditional or modern form of Korean theater. The most distinctive formal trait of Yeoseong Gukgeuk is that all performers are exclusively gendered female. Each actor’s drag-technique in playing a man varies according to their own analysis and understanding of masculinity, critically deconstructing the oppression-bordering conventions around gender, tradition, and historical consciousness.

The wall features two video monitors, each set with poster graphics that are taken from existing photo archives of Yeoseong Gukgeuk. The first set examines the gender expression of Lee So-ja, a first generation actor who used to play the Gadaki (male villain), including the actor’s conflicts and contradictions regarding gender roles. This is a non-chronic archive of the queer body that includes processes of superposition, division, glamorization and modification. The other set examines the memory of Cho Young-sook, another first-generation actor who mainly played the role of Sammai (comic supporting role/sidekick) (the graphic images are taken from Cho Young-sook’s personal archive.) The video is a documentation of the artist’s first theater performance entitled (Off) stage/Masterclass (2013), which was derived from the artist’s earlier Yeoseong Gukgeuk Research. It contains an oral history of Cho Young-sook in relation to modern Korean history, revealing a particular mode of transfer not exclusive to only traditional performance technique between generations, but also to gender representation within and beyond social norms therein.

This form of female theater can be observed in the histories of modern East Asian regions including Korea. The subject allows one to face head-on the desire found in Yeoseong Gukgeuk, as both invented and interpellated in the social space at the birth of the modern nation state and which surpasses the firm dichotomy in gender performance and the ideology that governs the dynamics of the formation and the exclusion of tradition. The artist deliberately puts on hold the existing history and writing methodologies of Yeoseong Gukgeuk and situates herself in/side the discourses and memories of Yeoseong Gukgeuk. She fills the inactivated time with an awareness unto the viewer of the massive space and the bodily movement of performance. Her emphasis is not given to the restoration of the intrinsic legitimacy of Yeoseong Gukgeuk. Rather, modification to the senses deployed by jung’s practice underlines the political power of more anomalous and queer artistic practices.

Lieko Shiga

Rasen Kaigan series, 2009-2021

Portrait of Cultivation, 2009

Mother’s Gentle Hands, 2009

Garden of Tears, 2010

Rasen Kaigan (No. 36), 2010

Rasen Kaigan (No. 27), 2012

C-prints, dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist

Lieko Shiga’s photographs appear as dreamscapes. They gain much of their visual power from the unusual interplay between light and color and the way in which her motifs often seem to defy physical laws such as gravity. She often photographs nocturnal landscapes that are both enchanted and haunted, invoking an emotionally and psychologically complex, contemporary inner landscape. The works also elucidate the ancient relations between mysticism, spirituality, and folklore, gesturing to Japanese traditions and beliefs while also transforming them. The Rasen Kaigan series was created in collaboration with local residents of the coastal town Kitakami in Japan’s Tohoku region, an area severely affected by the tsunami in 2011. Over the course of four years, Shiga acted as the city’s official photographer. The works in this series do not portray the disaster, but rather, explore a different kind of reality—a reality where the present exists only in dialogue with the past and with the spirits of the land. Shiga captures invisible complexities while at the same time invoking the artistic legacies of Surrealism, Land Art, sculpture, and experimental film. Her photos also recall earlier works such as Masatoshi Naito’s photographs of Japanese folklore. Shiga depicts the contemporaneous reality of the modern and the non-modern, giving visual expression to the tense and complex conditions surrounding the status quo. Shiga’s work conjures the idea that we, as subjects of modernity, stand on unstable and, ultimately, haunted ground.

Against Waves, 2019

Single-channel video, sound, 14:53 mins

Courtesy of the artist

Hwayeon Nam’s recent artistic research has investigated the history of the famous cosmopolitan choreographer and dancer in East Asia, Choi Seung-hee (1911–1969), with a specific focus on the period after 1941 when she defected to North Korea and the subsequent change to her art. Choi’s artistic life encompassed complex cultural positions, including internationally acclaimed dancer, cosmopolitan, Japanese collaborator, and communist. After touring around Europe, North America, and Latin America, Choi declared her ambition to invent a uniquely modern East Asian dance, one that transcended the boundaries of Joseon (Korea). Japan initiated the Pacific War in December 1941, the year that Choi returned to Korea; it was during this period that she performed for Japanese soldiers in China as a part of their morale-boosting campaign. At the same time, she announced new works inspired by classical Japanese musical drama noh (콘) and Japanese court dance bungaku (校楽). Living mostly in China during the War, Choi emphasized the importance of modernizing Peking opera and the need to establish a new modern East Asian dance. During these tumultuous times, she witnessed Korea’s independence and the collapse of Japan and Beijing. In 1946, after the divide of the Korean peninsula, Choi defected to North Korea.

Against Waves (2019) is set in a unique phase of a Korean dance lesson and its transmission of the tradition within a community and its future generations; that is, Choi Seung-hee’s 1959 dance textbook Basic Korean National Dance and its influence to the Zainichi Korean community in Japan (permanent ethnic Korean residents of Japan). The title of the work is taken from Choi Seung-hee’s choreographic work Against Waves (1956), which was written after she defected to North Korea. Inspired by the Korean traditional folk song of fishermen, its choreographic narrative is about a person enduring hardship as he attempts to cross the sea. Purportedly, Choi intended to criticize South Korea and the United States military’s role during the massacre of the Jeju Island April 3 uprising. Nam’s video connects Choi Seung-hee’s dance, her aspirations in promoting traditional Korean dance, to two Zainichi Korean dancers: Lee Kyung-hee who continues to teach Choi’s choreography to the students at a North Korean School in Japan, and “H,” a first generation Zainichi Korean dancer who secretly learnt Choi’s dance on a boat that goes between Japan and North Korea in the later 20th century. The unstable movements of learning a dance while balancing with ocean waves evoke the unsettling life and practices of Zainichi Korean pupils, with their strong desire rising above the restraints of political, nationalistic, and ideological barriers. Through this video, Nam forms a community across time and movements, connecting Choi with the next generation of pupils of Lee Kyung-hee and H in their precarious and determined footsteps. While dance on a repatriation ship to the North in the 1950s to 70s reflects Zainichi Korean society’s precarious life and Choi’s unsettled aspiration, the work envisions a space that hosts performing bodies across generations—additional lives joining the memories—and the distant future following Choi’s footsteps.

Some Sense of Orders, 2017

Oil on linen, 12 ½ x 16 in

Courtesy of the artist

Oil on linen, 17 ⅞ x 20 ⅜ in

Courtesy of the artist

Oil on linen, 17 ⅞ x 20 ⅜ in

Courtesy of the artist

Oil on linen, 17 ⅞ x 20 ⅜ in

Courtesy of the artist

Oil on linen, 14 ⅞ x 17 ⅞ in

Courtesy of the artist

Even amidst the disappearance of many unique traditions, the form of Jesa (Confucian ancestor veneration rites) remains a South Korean tradition that cannot be discarded easily. Artist Young Min Moon has repeatedly depicted, in the form of small paintings, an image of a man in a suit prostrating. Recently, Moon has repetitively portrayed the typicality of the Korean rituals of Jesa. The series of paintings is a world where layers with disparate meanings emerge and perform différance on a single plane, completed as one compact scene where the diverse layers which are associated with Jesa—including death, mourning, family belongingness, and a sense of burden, duty, and responsibility—intersect.

Throughout the artist’s childhood, Jesa were the only moments through which he could find peace and safety in times that were rife with violence and commotion. Growing up in a home where Jesa customs were retained despite the predominance of the Catholic faith post-immigration to the United States, the rituals of Jesa remained acts of manifesting communal solidarity and cultural identity. In his repetitive paintings, however, Jesa constitutes a cultural symbol that cannot be clearly acquired or given a single definition; this, in turn, casts an emptiness or uncertainty. The ritual scenes can be viewed as going beyond meanings forged by tradition and the individual and as pictorial allegories of personal, social, and communal points of intersection that the artist—who has experienced both the modernization of South Korean society and a diasporic life—holds onto.

GALLERY TWO

Funerals under Neon Lights, 2014-ongoing

Liangzi offering prayer, Chongqing, 2014

Digital c-print, pigment ink on archival fine art paper, 18 ½ x 27 ¾ in

This project was supported by the Abigail Cohen Fellowship in Documentary Photography, Magnum Foundation & Asia Society (ChinaFile). Courtesy of the artist, KADIST collection

Funerals under Neon Lights (2014–ongoing) is a series which portrays images of transgender people taking on essential roles within traditional funeral scenes in rural areas in southern China. Bathed in a high contrast of light and dark, the illuminated splendor casts a captivating melancholy on the conditions of death. Visiting funeral ceremonies to console the dead and the living—guiding the dead towards heaven by way of dancing, singing, and throwing a feast—is a custom one can encounter in remote areas of China where the central government’s modernization has yet to have fully taken effect. This unique custom is also found in Southeast Asia societies, such as Vietnam. The ritual and act of condolence are highlighted by transgender people who perform as connectors, to surpass boundaries of life and death, just as they cross the boundary of the gender binary. This work reveals how liberal and unbiased gender perceptions and genderqueer culture are alive and well within Asian tradition, demonstrating how modern society produces gender norms as part of modern border-making projects. This also deviates from an understanding of Asian tradition as enmeshed in a typical, heterosexual patriarcal system and enables us to enter the liminality of tradition beyond the limits of Asian modernization.

Tales of the Bamboo Spaceship, 2019

Single-channel video 15:35 mins

Courtesy of the artist

Tales of the Bamboo Spaceship (2019) is an ongoing project in which Ming Wong attempts to connect two seemingly distinct cultural forms of Cantonese opera and science fiction literature. This latest iteration presents a narrative structure drawing from his research of the past five years into the history of Cantonese opera’s transition from stage to screen in the 20th century. Wong extends the speculative possibilities of the traditional Southern Chinese art form forwards—that is, towards alternative futures for communities tied by language and cultural memory through the lens of science fiction—as well as backwards—to the opera’s coastal roots in the 19th century, embedded in its traditional mythology surrounding the sea.

Spirit-Writing, 2016

Two-channel video installation, 9:45 mins

Produced by Le Fresnoy - Studio national des arts contemporains and co-produced by Liang Gallery.

Courtesy of the artist. Please note: this artwork is licensed by KADIST for its programs, and is not part of the KADIST collection.

The installation Spirit-Writing is the second work Chia-Wei Hsu devotes to a frog deity who was allegedly born in a small pond more than 1,400 years ago in Jiangxi, China, and whose original temple in Wu-Yi was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Marshal Tie Jia, as the deity is named, was forced to migrate, eventually settling on an island in the Taiwan Strait. To this day, the Marshal has continued to communicate with local villagers through a divination ritual. The ritual involves the villagers carrying a divination chair, through which the Marshal makes his declarations both in writing (in Chinese characters) and through knocking sounds. The work consists of a recorded interrogation of the deity, placed at the invitation of the artist in a “green room” equipped with multiple cameras and sensors for the purposes of motion capture. In the session, Hsu explains the process in making this artwork to the deity, and interrogates the shape of the destroyed, original temple, which has been reconstructed in a separate 3D computer simulation. The green screen is a generic technique used in film, creating a homogenous background for a scene that can then be replaced with a different image in the edit, thereby placing an image into any desired context. It might therefore be referred to as a paradigmatic modern image technology, mirroring modernity’s powers of displacement. The story of the displacement of the deity is thus indexed in the technological setup, which enables its de- and re-contextualization. The sensors and cameras capture the actual movements of the divination chair as the villagers carry it, displacing it into a digital model of an abstracted Cartesian 3D grid. The villagers who carried the structure, however, are excluded from this transposition. This simulation shows, simultaneously but on the opposite face of the screen that documents the interrogation, where the villagers and artist engage with the Marshal. This contrivance represents the ghostly or quasi-spiritual counterpart, the virtual “other world,” in which the deity might reside, and in which the lost landscapes of the past can be reconstructed and reclaimed.

Garden of Perfect Brightness, 2019

Single-channel video, 9:00 mins

Courtesy of the artist

Garden of Perfect Brightness (2019) is a video work that is situated in the only remaining ruins of the destroyed Summer Palace of the Qing Dynasty, located in the Haidian district in Beijing. In 1860, British and French troops ransacked and set fire to the Yuanmingyuan complex which consisted of 800 acres full of exquisite gardens, architectural heights, and precious art objects. Under the command of the infamous British Lord Elgin, more than a million objects were looted. These objects are now on display in more than fifty different European museums, mainly in Britain and France. The violent event marked the end of the second Opium War and the start of the ruination of the imperial complex. In the film, Guépin focuses on the historical, geopolitical relationships between China and Europe through the lens of the remains of the Rococo style ruins (designed by Giuseppe Castiglione). These buildings only made up 2% of the overall architecture but are now used to represent the estate as a whole since no Chinese buildings survived the ages of destruction. In his practice, Yoeri Guépin questions historical and ethical notions regarding the ways in which objects relate to their environment, their modes of (re)presentation, and their varying interpretations in different moments of time.

Yoeri Guépin’s artistic research has developed through his involvement with historical trajectories of knowledge production such as archaeology and anthropology, given his investment in the writing of history through objects. Through collecting and translating objects, artifacts, and stories, and subsequently working to appropriate and recontextualize their originary meaning(s), he reveals the governing structures of these systems and how knowledge is represented through symbolic objects.

GALLERY THREE

Hotel Aporia, 2019

Single-channel video, 84:00 mins

Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery

Hotel Aporia (2019) explores the histories and biographies related to the Kirakutei, a Japanese-style inn and restaurant in Toyota city, Japan that operated between Japan’s Taisho and Showa periods. Originally a site-specific installation with six-channel video and automated fans, lights, transducers and a show control system, Hotel Aporia is presented as a single-channel presentation at KADIST.

Before the Pacific War, the Kirakutei was frequented by sericultural industry workers, wartime naval officers, and by employees of the auto industry after the war. Towards the end of the war, members of the Kamikaze Kusanagi Unit had a final dinner at the inn before their suicide mission against the United States Navy fleet in Okinawa. The characters in Hotel Aporia include members of that particular attack unit, wartime Kyoto School philosophers, and cultural workers, including film director Ozu Yasujiro and animator Yokoyama Ryuichi, who were both dispatched to Southeast Asia as members of the Propaganda Corps. These characters’ diverse lives and fates help us understand the multitude of forces and the complex and often contradictory ideological and historical backdrops of those tumultuous years during which militant nationalism was inextricably intertwined with attempts to overcome modernism and promises of liberation from Western colonialism. Hotel Aporia is the stage on which concealed histories are awakened. In this work, various conflicting contexts, wavering between buried memories and forgotten records, are pieced together; layers of consciousness, including reference to those who tragically lost their lives, unfold and find unexpected resonance. Here, historical facts appear in front of the viewer in the full force of their tragedy, yet the circumstances are woven together as a dazzling fiction, like a gathering of mysterious ghosts.

Ho Tzu Nyen has a wide-ranging artistic practice, including film, installation, and theatrical performance. His work engages with Asian histories, often by mobilizing an accumulation of images and texts to untangle and reveal their underlying contradictions and complexities. In deploying a multitude of technologies, Ho has also addressed the politics inherent to them.

NOTE: Texts on siren eun young jung, Tomoko Kikuchi, Young Min Moon, Hwayeon Nam, and Gala Porras-Kim by Hyunjin Kim. Texts on Yoeri Guépin, Ho Tzu Nyen, Seugi Lee, and Ming Wong by the artists. Text on Chia-Wei Hsu and Lieko Shiga adapted from the exhibition 2 or 3 Tigers, HKW (Berlin, 2017; Hyunjin Kim and Anselm Franke).

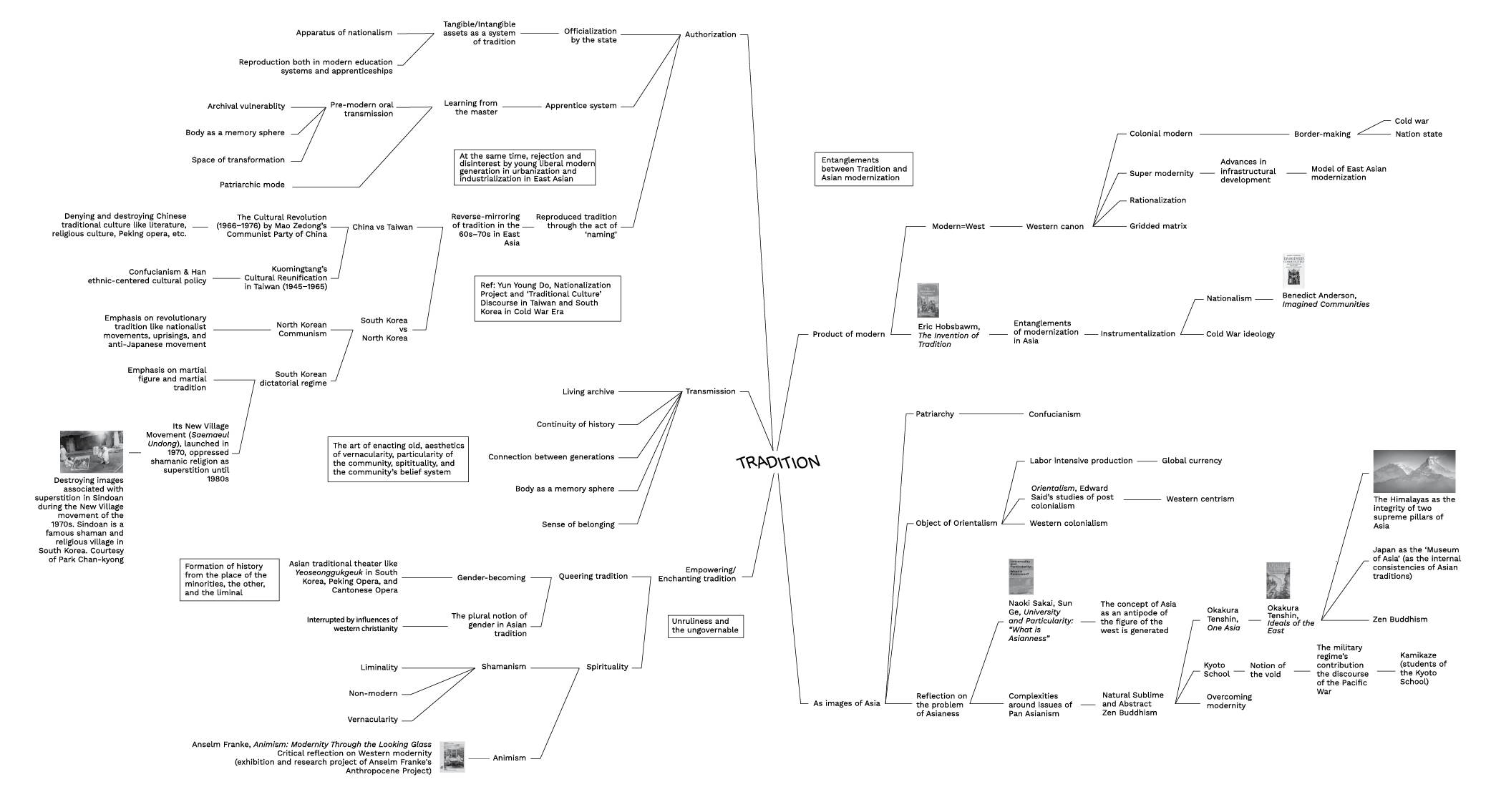

MIND MAP

PROGRAMS + SCREENINGS

Talk by Curator Hyunjin Kim

Wednesday, April 6, 2022, 7:30 pm

California College of the Arts, 195 De Haro St, San Francisco, CA 94103

Co-hosted by KADIST San Francisco and the Graduate Curatorial Practice Program at California College of the Arts. Registration required.

Frequencies of Tradition, Monthly Film Screenings

Wednesdays, April 20, May 18, June 15, July 13, 2022

All screenings start at 6:45 pm (doors open 6:15 pm*)

Little Roxie Theatre, 3117 16th Street, San Francisco, CA 94103

Tickets are $5, all proceeds go to the Roxie Theatre. Purchase tickets here.

Fiona Tan, Ascent (2016), 80:00 mins

Wednesday, April 20, 2022

Ascent (2016) reflects on Japan’s Mount Fuji and its great significance to the country and its people. Tan combines found images with a fictional narrative in which two protagonists climb Mount Fuji across geographical, temporal, and cultural divides. The breathtaking film is made entirely with heterogeneous stills; photographs, and archival materials revealing a unique realm in which still photography and film are joined together. The story, culminating with the ascent to the top of the mountain, unfolds across unexpected paths, alternating between narration and history, from Western imperialism to modern tourism, from the early days of photography to the present day.

Jane Jin Kaisen, Community of Parting (2019), 72:22 mins

Wednesday, May 18, 2022

Community of Parting (2019) invokes the ancient Korean shamanic myth of the abandoned Princess Bari and employs female Korean shamanism as a mode of ethics, aesthetics of memory, and mutual recognition. Rooted in the oral storytelling of the myth of Princess Bari, the story is one of filial piety. The film features imagery across various locations including but not limited to the DMZ, South Korea, North Korea, Kazakhstan, Japan, China, the United States, and Germany. Combining shamanic ritual performance, nature and cityscapes, archival material, aerial imagery, poetry, voiceover, and soundscapes, the work is configured as a multiscalar, nonlinear, and layered montage loosely framed around Bari’s multiple deaths. Both intersubjective and deeply personal in her approach, Kaisen treats the myth of the abandoned princess as a gendered tale of migration, marginalization, and resilience recounted from a multi-vocal perspective.

Wang Tuo, Tungus (2021), 66:00 mins

siren eun young jung, Deferral Theater (2018), 35:00 mins

Wednesday, June 15, 2022

Tungus (2021) is set against the historical backdrop of the Siege of Changchun, a military blockade with a suppressed history of the 1948 Kuomintang-Communist Civil War in China. In this quiet war without fire and smoke, hundreds of thousands of civilians, caught in the middle ground of beliefs and ideologies created by the military encirclement of the two armies, were killed through starvation. As two soldiers from the Korean Independent Division of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army try to flee Changchun, they gradually realize that they are caught in overlapping time and space at the site of Jeju Island, where, in the shadow of the Korean war, the Jeju Uprising has just occurred. Simultaneous to this sequence, a middle-aged scholar who refused to flee the city of Changchun returns to the May 4th Movement of 1919 in a starvation-induced hallucination. Through these forgotten historical narratives, Wang Tuo illustrates how hunger-based hallucinations informed by a shared collective experience lead to a reshaping of the power of the psyche mired in historical trauma. At the same time, the roots of contemporary geopolitical crises in Northeast Asia—buried deep in recent history—are gradually unfolded and retraced.

siren eun young jung’s Deferral Theatre (2018) intertwines the artist’s research into modes of queer resistance in South Korea, with particular attention paid to the Yeoseong Gukgeuk, a traditional Korean opera in which all of the roles are played by women. The radical and temporal “border-crossing” qualities of gender fluidity and the cultural lineage of queer subversion within performative spaces are animated through a critical deconstruction of Korean history, tradition, and gender norms.

Ko Sakai & Ryusuke Hamaguchi, Storyteller (2013), 120 mins

Wednesday, July 13, 2022

Ryusuke Hamaguchi and Ko Sakai’s Storyteller (2013) is the third film of the Tohoku Trilogy, a series which came out of interviews with residents of the northern region of Tohoku, Japan, an area heavily affected by the earthquake and tsunami in March 2011. Storyteller presents the rich folk tradition of storytelling by these inhabitants through victim dialogues and testimonies. Considering storytelling as an empowering process, the film documents and explores how the act of telling renders a past event into pluralities of present and future for the ravaged community. Folk storytellers Ito Masako, Sasaki Ken, and Sato Reiko gather at Kurikomayama in Miyagi Prefecture, and folklore scholar Ono Kazuko, the founder of Miyagi Minwa no Kai, plays the role of interviewer as they share a series of fantastic and outlandish tales with the community, including a story of a girl who marries a monkey.

*Come early! Each screening is preceded by original music and a sound mix curated by Topazu (Infinite Beat – San Francisco), with Annie Chen (Teaphile, Zhuang B – Oakland), Nihar (Left Hand Path, TVOD – San Francisco), and Aaron J (Sure Thing – Boston).

Please check our website at www.kadist.org for more details.

READINGS

*Books available for purchase at Dog Eared Books, 900 Valencia St, San Francisco.

*Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso, 1998.

*Calichman, Richard. Overcoming Modernity Cultural Identity in Wartime Japan. Columbia University Press, 2008.

*Esherick, Joseph W. The Chinese Cultural Revolution as History. Stanford Univ. Press, 2007.

Franke, Anselm. Animism. Sternberg Press, 2010.

*Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger, editors. Canto Classics: The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Hui, Yuk. Art and Cosmotechnics. e-flux, 2021.

Jackson, Andrew David, et al. Invented Traditions in North and South Korea. University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2022.

Kim, Chongho. Korean Shamanism: The Cultural Paradox. Routledge, 2019.

*Okakura Kakuzō. Ideals of the East: The Spirit of Japanese Art. Dover, 2004.

Park Chan-Kyong: Red Asia Complex. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea, 2019.

Kyoto School related

*Nishida, Kitaro. Intelligibility and the Philosophy of Nothingness: Three Philosophical Essays. Pantianos Classics, 2020.

*Tanabe, Hajime, and Yoshinori Takeuchi. Philosophy as Metanoetics. Chisokudō Publications, 2016.

Williams, David. The Philosophy of Japanese Wartime Resistance: A Reading, with Commentary, of the Complete Texts of the Kyoto School Discussions of ‘the Standpoint of World History and Japan’. Routledge, 2016.

Queer, Tradition, Asian Performance

Liu, Siyuan. Transforming Tradition. the Reform of Chinese Theater in the 1950s and Early 1960s. The University of Michigan Press, 2021.

*Wilcox, Emily. Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy. University of California Press, 2018.

BIOGRAPHIES

CURATOR

Hyunjin Kim is a curator and writer and was recently Artistic Director of Incheon Art Platform (IAP). Kim was KADIST’s Lead Regional Curator for Asia (2018-2020), curator of the Korean Pavilion, Venice Biennale (Venice, Italy, 2019), and Director for Arko Art Center (Seoul, 2014-2015). Her curatorial projects include 2 or 3 Tigers, HKW (Berlin, 2017); Tradition (Un) Realized, Arko Art Center (Seoul, 2014); Plug-In #3-Undeclared Crowd, Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands, 2006). Kim has also commissioned and written about artists including Jane Jin Kaisen, siren eun young jung, Nina Canell, Hwayeon Nam, Jewyo Rhii, and Seoyoung Chung. She served as an advisor for Haus der Kulturen der Welt (Berlin, 2014-2016) and as a jury member for DAAD artist residency (Berlin, 2017- 2018).

EXHIBITING ARTISTS

Chung Seoyoung (b.1964) represented Korea at the 50th Venice Biennale (Venice, Italy, 2003) and has held solo exhibitions at Ilmin Museum of Art (Seoul, 2013); Atelier Hermès (Seoul, 2007); Portikus (Frankfurt, Germany, 2005) and Art Sonje Center (Seoul, 2000). She has participated in several group exhibitions including the 8th Seoul Mediacity Biennale (Seoul, 2014) and the 4th and 7th Gwangju Biennales (Gwangju, 2002/2008). Her works are included in the collections of various public and national museums and institutions in South Korea, including the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul Museum of Art, Gyeonggi Museum of Art, and Art Sonje Center.

Yoeri Guépin (b.1983) emphasizes research and often involves historical trajectories of knowledge production such as botany, archaeology, anthropology, or the writing of history through objects in his work. Central to his practice is working with museum collections and archives as a site of knowledge production and their historical vernacular to colonialism. Guépin’s projects often materialize in performative settings involving elements of film, text, or objects, sometimes activated at a specific site. Guépin holds an MA from the Dutch Art Institute in 2013 and their work has been presented in several exhibitions and symposia such as TENT Rotterdam (Rotterdam, Netherlands, 2019), Akademie Künste der Welt (Cologne, Germany, 2018), and Institute for Provocation (Beijing, 2018).

A plethora of historical references manifested through theatrical tableaus and animation, and dramatized by musical scores, make up the pillars of Ho Tzu Nyen’s (b.1976) complex practice. Each work unravels unspoken layers of Asian and Southeast Asian histories whilst equally pointing to our own personal unknowns. Ho has been widely exhibited, with solo exhibitions at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art (Aichi, Japan, 2021); Crow Museum of Asian Art (Dallas, Texas, United States, 2021); Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (Yamaguchi, Japan, 2021); Performing Arts Meeting in Yokohama (Yokohama, Japan, 2018) amongst others. He represented Singapore at the 54th Venice Biennale (Venice, Italy, 2011). Recent group exhibitions include Museum of Contemporary Art Busan (Busan, South Korea, 2019); Aichi Triennial (Aichi, Japan, 2019); Home Works 8 (Lebanon, 2019); Sharjah Biennial 14 (UAE, 2019); the 12th Gwangju Biennale (Gwangju, South Korea, 2018); National Gallery Singapore (Singapore, 2018); Dhaka Art Summit 2018 (Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2018); Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin (Berlin, 2017); Guggenheim Museum (New York, NY, United States, 2016) and Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane (Brisbane, Australia, 2016). Ho lives and works in Singapore.

Chia-Wei Hsu’s (b.1983) work interrogates the relationships of humans, materials, and places omitted from the perspective of conventional history. Hsu has had solo exhibitions at the Museum of National Taiwan University of Education (Taipei, 2019); Mori Art Museum (Tokyo, 2018); Industrial Research Institute of Taiwan Governor-General’s Office at Liang Gallery (Taipei, 2017); Position 2 at Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands, 2015), among others. Group exhibitions include the Eye Filmmuseum (Amsterdam, 2019); the Shanghai, Gwangju, Busan, and Sydney biennials (2018); 2 or 3 Tigers at Haus der Kulturen der Welt (Berlin, 2017); and the Taipei Biennial (Taipei, 2016). He was the curator of the 6th Taiwan International Video Art Exhibition at Hong-gah Museum (Taipei, 2018); THAITAI: A Measure of Understanding at Bangkok Art Center (Bangkok, 2012) and co-curated the Asian Art Biennial (Taichung, Taiwan, 2019) with Ho Tzu Nyen.

siren eun young jung’s (b.1974) practice is deeply engaged with feminism and LGBT rights. Her work reveals the subversive power of traditional culture and provides unique perspectives and documentation of important communities. She has participated in major exhibitions including the Biennale Jogja XVI (Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2021); the 12th Shanghai Biennale (Shanghai, China, 2018); Tokyo Performing Arts Market (TPAM)—Performing Arts Meeting in Yokohama (Tokyo; Yokohama, Japan, 2014/2018); 11th Taipei Biennial (Taipei, 2017); the 11th Gwangju Biennale (Gwangju, South Korea, 2016); the 8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (Brisbane, Australia, 2015-2016); Tradition (Un)Realized at Arko Art Center (Seoul, 2014); the 8th Seoul Mediacity Biennale (Seoul, 2014). She received the 2013 Hermès Foundation Art Award, 2015 Sindoh Art Prize, and 2018 Korea Artist Prize and participated in the exhibition in the Korean Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale (Venice, Italy, 2019). She lives and works in Seoul, South Korea.

Tomoko Kikuchi’s (b.1973) photographic and video works examine themes such as gender, life, death, war, and history as an accumulation of individual memory and focus on the people who live in the cracks of a dynamically transforming society. She has participated in exhibitions including TOP Collection: Scrolling Through Heisei Part 2 Communication and Solitude at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum (Tokyo, 2017); Seven Japanese Rooms Japanese Contemporary Photography at Fondazione Cassa Di Risparmio della Spezia (La Spezia, Italy, 2016); Medium of Desire An International Anthology of photography and video at Leslie-Lohman Museum (New York, NY, United States, 2015); Go-Betweens-The World seen through children at Mori Art Museum (Tokyo, 2014). She is the recipient of Terumo Art and Craft Fund Category: Contemporary Art (2016), Prix Pictet Japan Award (2015), and the 38th Kimura Ihei commemorative Photographic Award (2013). Kikuchi is based in Beijing, China.

Seulgi Lee’s (b.1972) practice connects senses of the vernacular found in diverse local cultures and traditions around the world with the essence of language. She employs folk subjects and collaborates with master craft artisans, such as the dancheong, moonsal, and Tongyeong nubi blanket artisans, as well as with the association of traditional basket weavers in Mexico. She was recently named the winner of the Korea Artist Prize 2020, co-organized by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art and SBS. She has held solo exhibitions at Gallery Hyundai (Seoul, 2018); and SSamzie Space (Seoul, 2004), and group exhibitions include the Alternative Space LOOP (Seoul, 2021), 12th Busan Biennale (Busan, South Korea, 2020); the Asia Culture Center (Gwangju, South Korea, 2017); the 10th Gwangju Biennale (Gwangju, South Korea, 2014); and the 3rd Paris Triennale (Paris, 2012). Lee is based in Paris, France where she also established and operated the alternative space Paris Project Room in 2001.

Young Min Moon (b.1968) is an artist and critic whose work reflects his migration across cultures and his awareness of the hybrid nature of identities forged amid the complex historical and political relationships between Asia and North America. Moon has participated in exhibitions at Sansumunhwa (Seoul), Art Space Pool (Seoul), Kumho Museum of Art (Seoul), Gyeonggi Museum of Art (Ansan, South Korea), Kukje Gallery (Seoul), Smith College Museum of Art (Northampton, Massachusetts, United States), and the Carpenter Center at Harvard University (Boston, Massachusetts, United States), among others. Moon’s essays on contemporary Korean art have been published Rethinking Marxism, Contemporary Art in Asia: A Critical Reader (MIT), and A Companion to Korean Art (Wiley), among others. He is an editor for the online journal Trans Asia Photography. Moon is a professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship and Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant.

Hwayeon Nam’s (b.1979) solo exhibitions include Mind Stream at Art Sonje Center (Korea, 2020); Abdominal Routes at Kunsthal Aarhus (Aarhaus, Denmark, 2019); Imjingawa at Audio Visual Pavilion (Seoul, 2017); Time Mechanics at Arko Art Center (Seoul, 2015). Nam represented Korea at the 58th Venice Biennale’s Korean Pavilion (Venice, Italy, 2019). Nam’s participation in group exhibitions include Reclamation, New Rocks, Stray Dogs, Birds, and Acoustics of the Garden at Incheon Art Platform (Incheon, South Korea, 2021); Reenacting History at National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Seoul, 2017); Wellknown Unknown at Kukje Gallery (Seoul, 2016) and Nouvelle Vague—Memorial Park at Palais de Tokyo (Paris, 2013) and has performed her piece Orbital Studies (2018) at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Seoul). Nam lives and works in Seoul, South Korea.

Gala Porras-Kim’s (b.1984) practice is made through the process of learning about the social and political contexts that influence how intangible things, such as sounds, language and history has been represented through different methodologies in the fields of linguistics, history and conservation. Her work comes from a research-based practice that considers the way institutions frame inherited codes and forms and, conversely, how objects can be used to make an official narrative through artifacts. Her work has recently been included in the 34th São Paulo Biennales (São Paulo, Brazil, 2021); the 13th Gwangju Biennial (Gwangju, South Korea, 2021); the 5th Ural Industrial Biennial (Ekaterinburg, Russia, 2019), and the Whitney Biennial (New York, NY, United States, 2019). She was a recent David and Roberta Logie Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University and current artist in residence at the Getty. Porras-Kim lives and works in Los Angeles.

Lieko Shiga’s (b.1980) practice is based on an instinctive feeling of unease with the convenience and automation of daily life. She has developed an artistic approach that links questions about the nature of the photographic medium with fundamental questions about life and the means of expressing oneself. Shiga received the coveted Kimura Ihei Photography Award in 2008. Her works were shown in the group exhibition In the Wake: Japanese Photographers Respond to 3/11 at the Museum of Fine Arts (Boston, Massachusetts, United States, 2015). Shiga made the New Photography 2015 shortlist of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Through a re-telling of world cinema, popular culture, and re-readings of cultural artifacts from around the world, Ming Wong’s (b.1971) practice explores the politics of representation and how culture, gender, and identity are constructed, reproduced, and circulated. His work has been shown at the Asian Art Biennale (Taichung, Taiwan, 2019); Times Art Center Berlin (Berlin, 2019); the 11th Busan Biennale (Busan, South Korea, 2018); Dakar Biennale (Dakar, 2018); Dhaka Art Summit (Dhaka, 2018); Para Site (Hong Kong, 2018); the 17th and 20th Sydney Biennale (Sydney, 2016/2010); and the 8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (Brisbane, Australia, 2015–2016) among others. He has had solo exhibitions at ASAKUSA (Tokyo, 2019) and Shiseido Gallery (Tokyo, 2013); Passerelle Centre d’art contemporain (Brest, France, 2016); UCCA (Beijing, 2015); and REDCAT (Los Angeles, California, United States, 2012). He represented Singapore at the 53rd Venice Biennale (Venice, Italy, 2009). Wong lives and works in Berlin and Stockholm.

MONTHLY FILM PROGRAM ARTISTS

Fiona Tan (b.1966) studied at the Rietveld Academie and at the Rijksakademie voor beeldende kunsten. Over the past twenty years, her video installations, films, and photographic works have gained international acclaim and have been exhibited internationally. She represented the Netherlands at the 53rd Venice Biennale (2009) and she took part in the 12th Venice Architecture Biennale (2010). Presentations of her work have included Documenta11 (Kassel, Germany, 2002) as well as many international biennials. Her work is included in collections such as the Tate Modern, Guggenheim, Centre Pompidou, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, MCA Chicago, and Schaulager, Basel. Her mid-career retrospective, With the Other Hand opened with a double solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Krems (Austria, 2020–2021) and the Museum der Moderne Salzburg (Salzburg, Austria, 2020–2021). Tan is based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Jane Jin Kaisen (b.1980) works across different media, including film, video installation, photography, and performance, to engage themes of memory, migration, and gender through poetic and non-linear storytelling. Kaisen represented Korea at the 58th Venice Biennale’s Korean Pavilion (Venice, Italy, 2019) and has participated in the Liverpool Biennale (Liverpool, United Kingdom), the Gwangju Biennale (Gwangju, South Korea), and the Jeju Biennale (Jeju Island), among others. Kaisen has an MFA from the University of California, Los Angeles, an MA from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, and participated in the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program. Kaisen was born in Jeju Island, South Korea and lives in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Wang Tuo (b.1984) employs mediums of film, painting, and performance to examine the unreliable relationship between myth and history. Wang Tuo was an artist-in-residence at the Queens Museum, New York from 2015 to 2017 and was awarded a research residency at KADIST San Francisco in 2020. His recent solo shows include UCCA Center for Contemporary Art (Beijing, 2021); Present Company (New York, NY, United States, 2019); Salt Project (Beijing, 2017), Taikang Space (Beijing, 2016) and recent group shows at the 13th Shanghai Biennale (Shanghai, China, 2021); National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Seoul, 2020); among others. Wang is based in Beijing, China.

siren eun young jung see Exhibiting Artists.

Ko Sakai (b.1979) began producing films while studying at the Tokyo University of Agriculture. Ko entered the Graduate School of Film and New Media at the Tokyo University of the Arts in 2005. His films include Creep (2007) and Home Sweet Home (2006). Ko is based in Tokyo and Sendai, Japan.

Ryusuke Hamaguchi (b.1978) studied at the Graduate School of Film and New Media at the Tokyo University of Arts. His film Happy Hour (2015) received the 25th Japanese Movie Critics Awards Selection Committee Special Award, and his commercial debut, Even if I sleep or wake up (2018), was exhibited in the competition section of the 71st Cannes International Film Festival. In 2021, an omnibus work Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (2021) was exhibited in the competition section of the 71st Berlin International Film Festival and won the Jury Grand Prix. In the same year, Drive My Car (2021) was exhibited in the competition section of the 74th Cannes International Film Festival, and along with Takamasa Oe won the Japanese film script award. Hamaguchi is based in Kobe, Japan.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The in-depth discursive and curatorial research for the exhibition has evolved through previous collaborations, research exchanges, with co-curators and artists since 2012; Chan-kyong Park (the article Phantom of Minjok Art, 2014 and the work Kyoto School, 2017); Jang Youggyu, and David Teh (Tradition (Un)Realized, Arko Art Center, Seoul, 2014); Anselm Franke (Animism at the Ilmin Museum (Seoul, 2013) and 2 or 3 Tigers at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (Berlin, 2017); and the outstanding achievement and contributions with their commissions to Frequencies of Tradition by the artists siren eun young jung, Chia-Wei Hsu, and Ho Tzu Nyen.

Frequencies of Tradition would not have been possible without the support of the following institutions and individuals: David Teh, Sunjung Kim (co-organizers of the seminar on the Kyoto School, Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, South Korea, 2018); Anca Mihulet, Patrick Flores (co-commissioner of Chia-Wei Hsu’s Stones and Elephants, Singapore Biennale, Singapore, 2019); Kazuhiko Yoshizaki (collaboration for Ho Tzu Nyen’s Voice of Void, Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media, Yamaguchi, Japan, 2021); Tomoyuki Arai (Voice of Void Dramaturg, The Performing Arts Meeting (TPAM), Yokohama, Japan); Korean Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale (Venice, Italy, 2019; co-commission of siren eun young jung’s A Performing by Flash, Afterimage, Velocity, and Noise); Nikita Ying Qian Cai and Qiao Ling Cai (the exhibition Frequencies of Tradition, Times Museum, Guangdong, China); Mijoo Park, Soosung Lee, and Habum Lee (Incheon Art Platform, Incheon, South Korea), and thanks to the KADIST team, Marie Martraire, Jo-ey Tang, Shona Mei Findlay, Amanda Nudelman, Lauren Pirritano, and Jordan Stein.

—Hyunjin Kim